Visies voor het veld: Shari Aku Djifa Legbedje

Een veld dat traag durft zijn

Shari Aku Djifa Legbedje

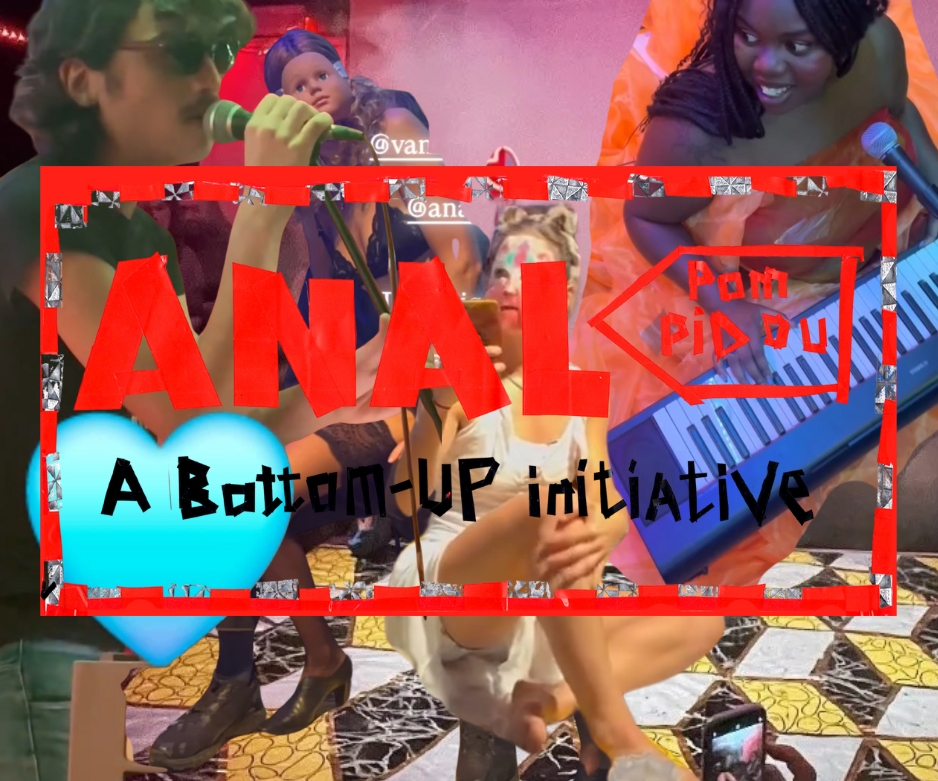

© Anal Pompidou

A cramped upstairs room above a Latin-American restaurant in the Sablon, sixty people crammed around tiny tables. For eight euros, three nights a week, Anal Pompidou turns this improvised stage into Brussels’ most chaotic cabaret, led by Simon Van Schuylenbergh’s delirious alter ego. Intimate, immediate and independent; it is perhaps the most vital art happening in this city wheezing under debt and bureaucracy.

It’s a Wednesday night in Brussels in early October and I’m sitting in front of a tiny stage in a packed room above Wallen, a Latin-American restaurant in the Sablon neighborhood. Together with a few friends and about sixty other people, I have come to see Anal Pompidou, a performance cabaret initiated by performer and theatre maker Simon Van Schuylenbergh in August 2025. It now takes place every Monday, Wednesday and Sunday night and always begins with an opening performance by Van Schuylenbergh, in which he steps into the equally exuberant and deeply frustrated character of Anal Pompidou.

It doesn’t take us long to get to the bottom of the cabaret’s premise. Van Schuylenbergh, as Anal, strips down to a fanny pack that only partially conceals his genitals and starts bragging about his asshole: it is so big, and so open! You can eat an artisanal croissant inside of him, ministers can shake their hands inside of him, children from the quartier can play a game of football inside of him! BRAFA and Art Brussels could happen at the same time inside of him. So much discourse can be produced inside of him, so many good ideas! Still, Anal wants more, something even bigger. He is “so high on art, and so low on money”. And aren’t we all?

Anal Pompidou follows in the footsteps of the centuries-old art form of the cabaret. Its unofficial tagline is “cabaret is the new museum”, and the primary target of its mockery is the inflated ambition of KANAL – Centre Pompidou, Brussels’ still-unopened museum of contemporary and modern art. Cabaret has always used humor and satire to critique the ruling class, and cabarets have also historically functioned as informal meeting places for artists and writers, a ‘low’ alternative to the stiff and uptight theatres and operas of Paris, Berlin or New York.

“There is no newsletter, no PR team, no development officer, and yet every night is sold out with a waiting list.”

Van Schuylenbergh previously initiated Ne mosquito pas1, a platform that invited artists to perform works they considered to have failed: cut scenes, bad jokes, ideas that never made it off the page. The idea was to counteract a blind spot of the institution, which only really cares about work that is “finished”. Anal Pompidou operates with a similar ethos of embracing experimentation and imperfection and draws from the pool of performers that gathered around Ne mosquito pas.

Van Schuylenbergh sets the tone for each cabaret night with his MC performance of Anal and invites three other artists to perform. Nobody has to audition or rehearse, and the performances don’t necessarily have titles. The program is announced via Instagram with reservations via email (“Dear Anal” is not a line I ever expected to type, but here we are); there is no newsletter, no PR team, no development officer, and still each night is sold out with a waiting list.

Back to said Wednesday night in October. We are sat around small round tables in classic cabaret fashion, but to fit everyone in, there are cushions on the floor and benches in the back. The stage is about the size of a modest dining room table and slants forward — in images, this makes it appear much bigger than it is — and covered with a wipeable plastic surface of faux terrazzo. The lighting, including neon flamingos, hearts and fairy lights can be adjusted to suit each performance, and a smoke machine is activated at regular intervals. Otherwise, the setup remains the same for each performer.

Van Schuylenbergh first appears as himself. He shares the origin story of Anal Pompidou, which developed out of a one-off performance at the artist-run space Winona before it became the premise for the cabaret. He then returns as Anal. He takes big rolls of duct tape and wraps them around his feet, using the cardboard rolls as heels. Returning behind the curtain stage, Anal stomps frantically back and forth in his prohibitive footwear, stopping at regular intervals to peek through the curtain, fix his eyes on the audience and exclaim: “What is thiiiiis?”.

The question of “What is this” has many answers, as Anal goes on to enumerate: Brussels? Sablon? A restaurant? A cabaret? Performance art? I once heard that surprise is the most boring emotion to convey, but the sense of camaraderie in the room combined with Van Schuylenbergh’s delivery touches a nerve. As Anal steps onto the stage, “What is thiiiiis?” morphs into repeated renditions of the word “shit”. Plastic turds fly across the room, and Anal seems possessed by a power greater than himself. He seems both enthusiastic and exhausted about this condition: He smokes eight cigarettes at once, then frantically sucks and chews on an entire tab of emerald lozenges. He inserts a sparkler into his asshole that an audience member must light for him, before launching into his monologue about the immensity of his asshole.

The audience is delighted and giddy, there are shrieks of laughter. It seems like we were all thirsty for some entertainment. Performance, whether in a contemporary art context or theatre, is often tedious and awkward, overly academic, or heavily edited. It feels like work. Here, we were in for a good time, at long last! But Van Schuylenbergh’s performance is just as much comedy as critique: as a body, a building and an institution, Anal’s attempts at self-optimization and medication are doomed to fail. He is helplessly porous and leaking, a condition that opens him up to experience pleasure as well as pain.

The second performer of the evening is Rosie Sommers. In lingerie and heels, Rosie recounts the journey of finding her sexuality. After many years of polygamous and queer experimentation, she has finally discovered who she really is: “a heterosexual cis woman, and I love it”. She points to her boyfriend in the audience, she loves his muscular arms and when he carries her suitcase up the stairs to their apartment. Rosie finds another heterosexual cis woman in the audience and asks her for permission to perform a lap dance on her boyfriend, “for practice”. Suddenly, Rosie becomes possessed by her traumatized inner child, symbolized by a mask that resembles the cut-out face of a Baby Born doll, which she asks audience members to stroke. Rosie then enters a feverish state, culminating in orgasm. Sommers’ skills as a comedic actor power this emotional rollercoaster of a performance. She is convincingly unhinged and deeply relatable at the same time, and I go with her even to places I am repulsed by.

“Anal Pompidou feels distinctly bruxellois. It is chaotic, DIY, international and self-reflexive.”

Following the intermission, the evening continues with Azertyklavierwerke, the alter ego of jazz pianist Alan Van Rompuy. Van Rompuy performs solo, switching between his electric keyboard, vocals and live looping. He performs his hit song ‘Durum’, which opens with the deadpan delivery of a typical exchange when ordering a dürüm in Brussels (“Sauce samurai-blanche/frites dedans oú apart? Dedans”) and continues with a chorus in Dutch about cruising through the city with your favorite fast food while missing someone you like. It’s a catchy pop song with a reggaeton beat and a kind of stoner energy. I feel a wave of affection for Brussels wash over me, a delightful and delusional sense of local patriotism that allows you to temporarily forgive and even embrace your city’s shortcomings.

In fact, all of Anal Pompidou feels distinctly bruxellois. It is chaotic, DIY, international and self-reflexive. Everybody has an accent and is a little sweaty. It captures a specific moment in this impossible city, where we don’t know if we are on the brink of something great or of total collapse.

The final performance of the evening is by Jonathan Franz, a spoken word monologue in ten parts. Franz arrives on stage as a drunk man clutching a glass of beer. The stage is empty except for Franz and his microphone, the thin mesh curtain behind him stays open. The man is desperate to communicate something but incapable of stringing together a full sentence. He then appears to sober up and begins to speak more coherently, with authority. He knows his references, moves from Molière to Roman emperors to Madonna, but the quotes are twisted or incomplete. He recounts surreal tales of rejection: “There was a partition in my room / splitting the room in two / I cut a hole in it for this one guy to come through / He never showed up”. Throughout, Franz stays fragmented and opaque, delivering passages that deal with absence, insecurity, and failure in both form and content. The work appears under the guise of autofiction but is more outward-looking than self-obsessed: how does it feel to exist in this world as someone who wants to make things and share them with others? Is it me who is failing or is the system stacked against me?

It’s a sobering note to end the evening on, but one that is poignant here. Anal Pompidou can exist because certain political conditions make it possible. Many of the artists involved can make their work thanks to the statut d’artiste through which they receive a modest monthly stipend from the state. As austerity looms on a federal level, the future of this social security is imperiled — and we don’t seem remotely equipped to provide an alternative path for artists who want to make ends meet, or dare I say it, make a decent living.

Like any effective satire, Anal Pompidou exposes a discrepancy in power. In this case, a cultural landscape in Brussels that is dependent on the many artists living here but seems unable to adequately support artistic production. The city’s finances are under increasing stress due to the political paralysis following the elections in June 2024, after which its administrators have failed to form a government. Structural funding for culture is delayed and uncertain, and long-term planning is impossible — not to mention the toll this vacuum is taking on infrastructure and social cohesion more broadly.

Meanwhile, KANAL Pompidou is not even open yet and its workforce dwarfs that of any other institution dedicated to contemporary art in the city. The costs of its construction have exploded the initial budget, now estimated to reach 230 million euros, a steep sum for a city that is drowning in debt. Regardless of whether KANAL will fulfill its many promises, for many artists, the dream of the institution is already broken — the idea that if you manage to pass through its gates, you will be protected and respected. As the recent decision of the Flemish government to dissolve the national museum status of M HKA shows, not even the institutions themselves are sheltered against the whims of political decision-making. And artists, whose work is the lifeblood of any museum and cultural activity, are certainly not being included in these conversations.

For now, Anal Pompidou is one possible answer to this disparity. The cabaret provides a platform that is independent from any formalized organization and financed through a cash economy: admission is €8 and the performers receive a symbolic fee. The restaurant providing the space is owned and run by Van Schuylenbergh’s boyfriend. Anal Pompidou is not about rejection or boycott — many of the artists, performers and writers involved are also presenting their works in institutions and understand that there is no way around them.

But here, something else is possible. Three times a week, peers share a stage with each other and are given the freedom to try out something new. They can be radical, political, or just plain silly in a way that doesn’t need to fit into a spreadsheet or translate to the language of bureaucrats and administrators. Anal Pompidou is intimate, immediate and perhaps the most vital art happening in this flawed but pulsating city.

Open almost every Monday, Wednesday and Sunday at 21h. See Instagram for the programme.

Participating chain of artists: Simon Van Schuylenbergh, Betül Sefika, Nathan Ooms, Chiara Monteverde, Osamu Shikichi, Maya Dhondt, Charlotte Nagel, Julia E. Dyck, Giulia Bonfiglio, Castélie Yalombo, Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe, Sophia Rodriguez, Sophie Melis, Spring Showers, Zoratheh00k3r, Giulia Piana, Anna Franziska Jäger, Hanako Hayakawa, Climate Change, Mira Maria Studer, Gio Megrelishvili, Marlla Araújo, Alice Igina Giuliani, Anna De Sutter, Steven Van Ham, Lucie Plasschaert, Astrid Sweeney, Micha Goldberg, Patric da Cunha, Lydia Mcglinchey, Maya Mertens, Oriana Ikomo, Adrien Di Biasi, Sophia Danae Vorvilla, Manizja Kouhestani, Rosie Sommers, Julian Gypens, Lea Petra, Thymios Fountas, Nathaniel Moore, Loucka Elie Fiagan, Misha Demoustier, Melody Van Gompel, Jonathan Franz, Helena Araújo, Gosie Vervloessem, Nathan Felix Rivot, Vivi Focquet, Azertyklavierwerke, Anna Vinkele, Bambi, Jana De kockere, Stefa Govaart, Charly Ange Fogaroli, Jacopo Buccino, Ondine cloez, Ehsan Shayanfard, Rodrigo Batista, Clément Corillion, Maxime Dreesen, Røsy del C, Breno Caetano, Louison De Leu, Kristina Nickel, Pierre-Louis Kerbart, Géraldine Haas, Ine Bonnaire, Jayson Batut, Dolores Hulan, Joeri Happel, Joke Caimo, Margarida Ramalhete, Drag Couenne, Arno Verbruggen, Drag Couille, Alphonse Eklou Uwantege, Désirée 0100, Sophia Bauer, Røsy del C, Steven Michel, Tomas Pevenage, Marco Labellarte, Ika Schwander +++

KRIJG JE GRAAG ONS PAPIEREN MAGAZINE IN JOUW BRIEVENBUS? NEEM DAN EEN ABONNEMENT.

REGELMATIG ONZE NIEUWSTE ARTIKELS IN JOUW INBOX?

SCHRIJF JE IN OP ONZE NIEUWSBRIEF.

JE LEEST ONZE ARTIKELS GRATIS OMDAT WE GELOVEN IN VRIJE, KWALITATIEVE, INCLUSIEVE KUNSTKRITIEK. ALS WE DAT WILLEN BLIJVEN BIEDEN IN DE TOEKOMST, HEBBEN WE OOK JOUW STEUN NODIG! Steun Etcetera.